Christ is nigh ...

Notes about the image (in English and German)

Oil on paper

Bernd Hildebrandt 2004

Christ is nigh ...

Thoughts on the Christmas picture 2004

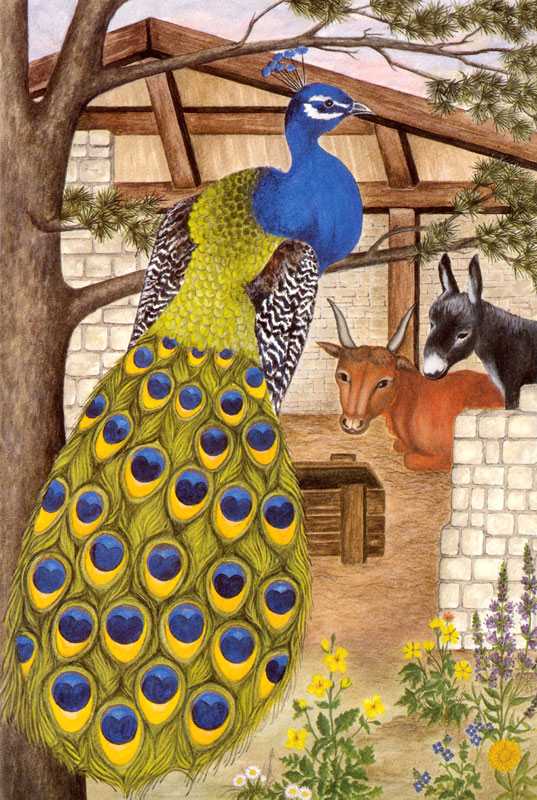

The picture is different from the uncountable Nativity depictions in Christian Art, although it is entirely made up from symbols which are common in Nativity scenes through the ages. The aim of artists in general, but notably of masters in the Italian Renaissance, was not just to illustrate bible stories, but to interpret and to make statements of faith. For this they used symbols, images whose hidden meanings were universally known in the Christian world of their time.

Contrary to tradition, my composition shows part of the stable in Bethlehem just ‘before’ the birth of Jesus. Note, the manger is still empty. What however is the meaning of the other features in this picture?

Here, as so often in religious scenes, the right side (left from the viewers point) emphasizes the Divine, whereas the left deals more with human responses. Classic examples are the paintings of the ‘Annunciation’, where the angel Gabriel invariably comes from the right.

In Nativity pictures structures of crossed beams mean “Here is holy ground”. The evergreen cedar tree points likewise to ‘holiness’, it is a symbol for God’s eternal grace, because its wood was deemed indestructible. The prophet Ezekiel uses the image of a cedar in a beautiful Messianic promise: This is what the Sovereign Lord says: I myself will take a shoot from the very top of a cedar and plant it; I will break off a tender sprig from its utmost shoots and plant it on a high and lofty mountain... (recommended reading: Ezekiel 17.22-24).

The prominent figure of the peacock may seem a strange choice for a Christmas picture. But there are precedents. The Italian masters Botticelli, Crivelli, Gozzoli, Lippi, Tintoretto and others, all show a peacock in scenes surrounding the birth of Christ. The peacock is an ancient and diverse symbol, with both, positive and negative notations. In Christmas pictures it is used to proclaim the creed that Christ is our Lord and Saviour from eternity to eternity. Since earliest Christian times the peacock is a symbol for Christ’s resurrection, because the bird sheds and renews his splendid tail feathers. In addition there is the legend, supported by a declaration from St. Augustine, that peacock flesh is incorruptible.

The broken stonework points to the fulfillment of the prophesy: On that day I will restore David’s fallen house; I will repair its gaping walls and restore its ruins (Amos 9.11).

Ox and Ass we expect in pictures of the Nativity. They refer to the reproach in Isaiah 1.3: The Ox knows his master, the donkey his owner’s manger, but my people do not understand.

And then there is a selection of plants in the foreground. They too feature in old Christmas pictures. Instead of the stately Lilly for instance, 15th century artists felt that the modest Daisy is a better symbol for the innocence of the child Jesus. Closest to the peacock stands the Greater Calendine, a medicinal plant used for ailments of the eyes. Here it means, that this weed opens the eyes; it cures spiritual blindness. The smaller plant with the blue flowers is Veronica. Its symbolic meaning comes from a play upon words. Veronica -”vera unica medicina” - Christ is the only true cure. Nearest to the wall the medicinal plant Herb Bennet points to Jesus, the healer of the world. Next to it we have Hyssop, mentioned in Psalm 51.7: Cleanse me with Hyssop and I shall be clean. This means literally ‘un-sin me’. And right in the corner we see the Cottage Marigold, a symbol of salvation.

Salvation is the joyous news throughout this unusual Christmas picture.

Bernd Hildebrandt, Christmas 2004

In Erwartung des Kommenden

Hinweise zum Weihnachtsbild 2004

Nehmen wir einmal an, daß dieses Bild einen Stall zeigt, der kurz darauf zur Geburtstätte Jesu wird. Die Krippe ist ja noch leer. Es soll eine Bilderpredigt sein, ein Zeugnis des Glaubens an Jesus Christus, eine Art Weihnachtsbild von Ostern her gesehen. Dies war jedenfalls das Anliegen der großen Meister der italienischen Renaissance, Botticelli, Crivelli, Gozzoli, Lippi, Tintoretto u.a., die nicht nur darstellten, sondern gleichzeitig deuteten. Meine Komposition zeigt ein paar Beispiele aus der Fülle der Sinnbilder, die für die alten Meister bereits Tradition waren. Es ist eine Zusammenschau von alttestamentlichen Weissagungen, neutestamentlichen Glaubensaussagen und die auf Christus weisende Symbolik aus geistlichem Volksgut.

Die rechte Bildseite (vom Beschauer aus links) betont, wie oft in religiösen Bildern, das Göttliche selbst und die linke Seite mehr das Bekenntnis zu ihm. Gekreuzte Balken bei Krippenbildern sagen: “Hier ist heiliges Land”. Die Zeder, als immergrüner Baum, ist in gleicher Weise ‘heilig’. Ihr Holz galt als unverweslich, Sinnbild immerwährenden Heils (vgl. Psalm 92, 13-16). Die Zeder ist gleichzeitig Symbol vom Versprechen der göttlichen Gnade. Beim Propheten Hesekiel finden wir die Zeder in eindrucksvollen Versen (Hes. 17,22-23) einer messianischen Verheißung genannt.

Die Hauptanregung zur Bildgestaltung kam durch die seltsam anmutende Tatsache, daß die vorher erwähnten Künstler alle einen Pfau in ihren Weihnachtsbildern haben. Die symbolische Bedeutung dieses Vogels ist so alt und vielseitig, daß man hier nicht alles beschreiben kann. In die Bilder um die Geburt Jesu kam er jedenfalls als Symbol der Auferstehung, weil er seine schmucken Federn abwirft und wieder erhält. Dazu kam die Legende, unterstützt durch die Erklärung des Kirchenvaters Augustinus, daß Pfauenfleisch unverweslich sei. Ein Sinnbild für Gottes Gnade durch Jesus Christus von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit.

Das zerbrochene Mauerwerk deutet auf das Wort aus Amos 9,11: “Zur selben Zeit will ich die zerfallene Hütte Davids wieder aufrichten und ihre Lücken verzäunen”. Die Anwesenheit von Ochs und Esel im Weihnachtsbild ist so bekannt, daß ich hier nur auf den Tadel in Jesaja 1,3 hinweise.

Kurz seien noch die Pflanzen erwähnt, die ebenfalls alten Weihnachtsbildern entnommen, hier den Vordergrund des Bildes ausfüllen. An Stelle der stattlichen Lilie wählte man im 15. Jahrhundert das bescheidene Gänseblümchen als Bild für die Unschuld des Jesuskindes. Daneben das Schöllkraut, ein Heilmittel für Augenleiden. Symbolisch bedeutet es: “Das Kraut öffnet die Augen. Es heilt eure geistliche Blindheit”. Die kleinere gelbblühende Pflanze unter der Mauer ist die Nelkenwurz, auch “Allerweltheil” genannt. Sie weist auf Jesus: “Dies ist das Heil der Welt”. Daneben steht Ysop, genannt in Psalm 51.9: “Entsündige mich mit Ysop”. In Krippenbildern weist Ysop auf Jesus: “ Dieser befreit uns von Sünde”. Die kleine Pflanze mit den blauen Blüten ist Ehrenpreis, botanisch Veronica genannt. Aus Veronica ergab sich des Wortspiel: “Vera unica medicina”, d.h. Christus ist das wahre einzige Heilmittel. Und letztlich steht da die Ringelblume, auch “Sonnenbraut” genannt. Sie ist Heilpflanze und Sinnbild der Erlösung.

Sinnbild der Erlösung, das ist die gesamte Botschaft dieses ungewöhnlichen Weihnachtsbildes.

Bernd Hildebrandt, Weihnachten 2004